NRBQ Photos

CONVERSATIONS

Scott Ligon: Concerned Citizen

"Part Three of my conversation with Terry is coming soon. Meanwhile, here's a chat I had with Scott on September 1, 2011." -Shirley Haun

(Note: You can read Part One and Part Two with Terry below Scott's interview.)

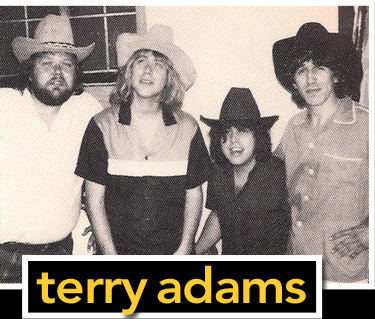

pictured: Young Scott

Shirley: Most NRBQ fans are baby boomers - what year were you born?

Scott: I was born in 1970. I wasn't even alive while the Beatles were a group. It's awful, isnít it? Terrible (laughs). But you know, it's funny. I grew up in this household where records were a big thing. My brother Chris is a big record collector and my parents had a lot of albums, so I kind of just grew up in this big pile of records. Amongst those were pretty much all of the Beatles' records.

I bring the Beatles thing up because it's probably the place to start. I guess it is for a lot of musicians. It's funny because I can honestly say that I don't remember discovering the Beatles. They were always a part of my life. My girlfriend Sharon, she's 12 years younger than I am, born in 1982, and one of the things that brought us together was the fact that she's a huge Beatles fan. She discovered them when she was maybe thirteen or fourteen. I just find that so interesting, to think of a young girl in the mid-1990s discovering the Beatles for the first time, just wondering what brought her to that.

It's really a defining thing for a lot of people. It even gave her a sense of direction in her life (laughs), in junior high or high school. She liked to draw and she would spend the whole day drawing pictures of the Beatles.

And I'm kind of the same way. I always thought I was going to be a Beatle. From the time I was a kid, I just thought, "Oh, well, I'll just do that." (laughs) And I even remember the moment that I decided that I was going to be a musician. It was an actual intellectual decision that I made. I remember noticing that Paul McCartney played the bass left-handed. And I thought that was so cool! I thought that was the coolest thing, that he played differently than everybody else did. And at that moment, I remember thinking, "That's what I'm gonna do. I'm gonna play and I'm gonna do something different."

Shirley: Are you left-handed Ė was it that?

Scott: No, I tried it for awhile and it didn't make any sense. So I stopped that pursuit (laughs). I just made the connection that he was playing his instrument differently than the other guys. And for some reason, I always remember that as being the moment that I decided that I wanted to play music.

Shirley: As you were discovering the Beatles, did you have the awareness of them as individuals? Did you have your favorite Beatle?

Scott: Definitely. For myself, for some reason, I related to Paul when I was a kid. I'm not really sure why. Maybe it started with him playing his instrument differently than the other guys. As I grew older, I became more intrigued by the other members of the band, in particular, John.

That's one of the things that was so great about that band, that you really could have a favorite. I always felt the same away about NRBQ. I thought they were one of the few bands that were in that mold, where you really could have a favorite. There's an awful lot of bands nowadays where it's just a guy that writes all the songs and he's got his back-up band. And generally people don't even know the name of the bass player.

But I still get really excited seeing photographs of the Beatles or seeing the instruments or even when a new record's coming out or a new repackaging of old records, whatever (laughs). I still get really excited about that.

Shirley: How could you not be happy about the Beatles...

Scott: Yeah. I think that there have been other bands that have a similar sense of joy and happiness and sense of humor, you know. And I just thought NRBQ fit right into that.

Shirley: How did you differentiate your enthusiasm for those two bands, one hugely famous around the world and one, well, less so...?

Scott: Well, I discovered NRBQ when I was 18 and I'd already been playing music professionally. I had my first bar gig when I was in 7th grade. I had my own band when I was a really young kid and we were best friends, friends in my neighborhood. We all shared similar tastes and we all sort of had the same idea about what we wanted to do.

And then my parents moved and I went to high school in a different town, in St. Louis. So I kind of had to start over. And for some reason, I always liked happy music. That meant that my tastes tended to lean backwards, I guess (laughs). The music that other people my age were listening to didn't have anything to do with the things that I was interested in. So I had a hard time making music with people because you know, in the 1980s, everybody was into all of this crap, like heavy metal and, uh... I don't know what they were into but I know it wasn't what I was into. The Beatles led me to all this other stuff, the Everly Brothers and people like Buck Owens and.... They covered these people's music and so I learned a lot through the Beatles.

And my parents were really into jazz. So I kind of had that background going as well. My dad was really a huge fan of Dave Brubeck. Then I had my brother Chris, who was listening to all of this really interesting stuff. Chris was listening to things like Captain Beefheart, and the Residents, as well as pop music, like the Beatles or Sly and the Family Stone, but he also liked jazz, so I was already heading in the direction of liking all different kinds of music and the stuff that I tended to like had kind of a positive spirit about it.

I was having trouble finding people that I could communicate that with. And it's not something that I could really talk about. It's just something that you try to do through music.

So I was having some trouble, and I guess when I was about 18, my brother Chris one morning came into my room. I was asleep. He brought this album in and just put it on, and it was God Bless Us All. And I didn't know anything about it and he just put it on and we were listening to it and I was really intrigued by this. And I just thought, "Whatís going on here?" I couldnít figure out... Is this an old band, or a new band? Who is this?

And I guess maybe a week or two later he sent me a cassette tape that had a couple of songs off of At Yankee Stadium on it, and then I was really, really concerned (laughs). The first three songs on that album just really blew my mind. I just couldnít believe it.

This was in 1988. And I thought, "Man, Iíve gotta see what this is all about." So eventually we found out that they were coming to St. Louis so my brother and I went.

And it was a weird night. There weren't a whole lot of people there. But I just had this crazy thing happen to me that night when I saw them. It was just so revealing. And so moving... and yet it was very confusing for me because I really, really felt like, "Oh no. What am I gonna do?" (laughs) I really, really felt like I was supposed to be in that band. From the first time I saw them.

And so it was kind of this clarifying moment where I felt, "OK. This is what I've been talking about. This approach and this language, I understand it." And I knew it immediately. I knew that I knew these guys and I knew what they were doing. I don't know how I knew it, but I just felt like I did. But at the same time, I wasn't in the band. So it was very confusing.

I didn't know exactly what to do about it, other than just join up and go see them as much as possible and of course I went out and bought all the albums.

I was buying everything on cassette and driving around by myself learning all of these songs, driving around in my little Mazda listening to, I don't know, 25 albums or whatever it was, over the next couple of years. It just felt so familiar to me and at the same time I was always being surprised by the next song or by the next chord change or... I don't know, I just felt like I had some instinctual connection to what they were doing.

And like I said, it kind of haunted me for about twenty years (laughs). I was in a lot of different bands that I tried to be serious about but I always had this NRBQ thing hanging around on my shoulder, or my back, like a monkey on my back or something.

And I also had this strange connection with Terry, or at least I thought that I did. Terry always seemed like someone that I knew. Did you ever, when you were in school or even maybe at work or something, did you ever see somebody and the first time you see that person, you think, "I have to know this person?" Has that ever happened to you?

Shirley: Sure, sure.

Scott: Where you just have this instinctual thing where it's like, "I am going to know this person." (laughs) Well, I kind of felt that way about Terry from the very beginning and for the longest time, I thought I must be nuts or something. But you know, it ended up... I'm glad that I followed my instincts about it, because I ended up being right.

I don't know if I answered your question... There's so much to this.

The thing is, Terry kind of reminded me of my brother...Not only of my brother, but he also kind of reminded me of myself. The way Terry performed really reminded me of myself, because I was always a very animated performer. The thing that you could count on from me, more so than musicianship, was the fact that I'm going to give everything I have to this every time I play. And I recognized that in Terry.

And there were things that I noticed that he did that I knew that I kind of did also. Because you know, I'm a piano player as well. And the way I played piano before I had even seen Terry... like I said, I kind of had some identity issues with all of this (laughter) because it's so familiar.

I felt at one point in my life, that, "I have to either completely distinguish myself from this, or I have to be in this band."

This is something that has followed me for a long, long time. The fact that it's turned out the way that it has, you know... I don't think there's any mistake in it. None of this is an accident.

Terry came to Chicago in 2006, I think it was, with Steve and Tom and I just decided that I needed to be there for that and I needed to tell Terry how much I appreciated his music and to thank him for it. I didn't really know what was going on, but for some reason I had this strange feeling that I was never going to see him again. I had this feeling like, "I have got to tell him this."

I knew that the NRBQ thing was weird, they were pretty much broken up, no one was saying anything about it. And I had heard some weird things about Terry, that maybe he was sick, and I just thought, "Man, I gotta talk to him. I gotta thank him."

And the thing is it's so hard to do that at a gig. You know how that is. It's just the worst time to try to get through to anybody. But I managed to do it and maybe the timing of it... I guess a couple of the things that I said must have resonated with him in just the right way. And six months later, or whatever it was, I got a call.

Shirley: What was it like to get a phone call from him?

Scott: Well, it's funny because, I remember the night after we spoke at Fitzgerald's, Terry left and PJ O'Connell was there and he came up to me and he said, "Hey man. I think Terry really likes you." (laughs) He was kind of stroking me, it was funny. And I remember, that night, driving home with Sharon, thinking, "Yeah, maybe something will happen." And then it was like, "Oh come on. I can't be thinking like that. Just go on with what you're doing and whatever happens, happens."

And six months later, I came home one afternoon and I had some messages on my answering machine and one was from Terry and he said [Scott does a perfect imitation of Terry's voice], "Scott. I got your number from Bill Fitzgerald. It's Terry Adams, your leader. I'm callin' ya. Call me back." (laughter)

He said, "Your leader." "Your leader is calling you." You know, it was one of those things where your heart just sinks. It was the kind of thing where I felt like, "OK, I have to call back right away." I can't allow myself any time to think about this because I didn't want to have anything planned that I was going to say to him, you know what I mean? I was too nervous to do anything other than just call right back. So I didn't really allow myself much time to think about it. And I called back but I don't think he answered, I think I had to leave a message.

And as excited as I was, I have to admit that I wasn't completely shocked, you know? It's as though I kinda knew it was coming all along.

Our conversations, as far as I know, are what got me into the band, just the talks that Terry and I were having. It was either that or the two songs he heard me play on the piano at Fitzgerald's that night (laughs).

And this has a lot to do with that thing that I was telling you about before where I just kind of already knew this. I kind of already knew Terry. I felt like I already spoke his language.

It was funny, though, getting to know Terry over the phone was such a strange thing to do because we built this relationship over a couple of months of conversations and I have to admit that I wasn't really connecting the fact that it was that guy that I was used to watching on stage for all of those years. It wasn't until he picked me up at the airport, when I first went out there that it was really real. "Oh Jesus. That guy." (laughs)

And he was great, you know. I had that thing where I was thinking I know this plane is going to go down before I get out there and fulfill my destiny (laughs). But it didn't, luckily.

Shirley: Were you nervous?

Scott: I was nervous the way you'd be nervous being around anybody that you hadn't spent any real time around and you were now going to be in the car for 40 minutes, coming back from the airport. (laughs) Just sitting in these close quarters and I'm coming to terms with who he really is... But you know...

One of the things that I really appreciate about Terry and something that I've learned from him that I think is really interesting is that .... Terry isn't particularly interested in just filling up space with conversation. He doesn't just spit something out just to be saying something. He's OK with silence. I really appreciate that. I was always the person thinking, "Oh God, nobody's saying anything! Say something stupid..." just to be saying something, and that's really pretty stupid, actually.

But we went back to his house and we just sort of hung around and talked for awhile, and I probably drank some wine and we talked until midnight or something, 1 am, and then we started playing.

We went into his music room and he had some crummy little acoustic guitar for me to play (laughs), a tough situation... to be playing a bad instrument when you're playing with Terry for the first time.

We went in there and he just started raging on the piano and he started playing a really, really fast rag kind of thing, I don't remember what it was. It was really intense. I was actually hearing Terry for the first time up close. At first I was kind of just stunned for a second. I just sat there and listened to him, and then I remembered, "Oh shit. I've got a guitar in my hands, I'm supposed to play." And so I started playing and the next thing you know, three hours had gone by. I think we probably played forty-some songs that first night. It was mostly all his songs. I was suggesting things, requesting songs of his that I don't think he was expecting to play, and we were right into it the very first night.

Shirley: I have the sense that musicians playing with him have to be on their toes in a way that perhaps no other musician puts a band on their toes. Was it hard to keep up with him? What was that like?

Scott: I already knew that. One of the things that I learned from Terry before I ever met him was that pacing onstage. Because the thing is, until I was in this band, I was the leader of every band I was ever in. And I was the guy calling songs. Always have been. I just loved the way he worked. And that way of calling songs, the no setlist thing, keeping the energy going, and trying not to repeat yourself, and trying to make every evening as unique as possible was something that I'm very used to. And I got that inspiration from Terry and NRBQ. So it wasn't difficult for me. I expected it.

And I was really happy that when we first started playing, our first few rehearsals as a band, he didn't hold our hands at all. We were just thrown into the pool. He wasn't even saying the names of songs. He was working the way he always works, which is just going from one song right into the next.

And you know, some guys know what song it is, and maybe a couple of us don't (laughs), but you just, you know... He always works that way and I really appreciate the fact that he didn't feel that he needed to alter the way he works for our benefit. I thought that that was a very respectful thing for him to do... to believe in us, that Conrad and Pete and I could keep up with him.

Shirley: I've always been struck, even though from the beginning I felt that it was Terry's personality that was predominant in NRBQ, I still was struck by how much the spotlight was shared, how much everybody was expected to contribute. And how much love and attention was put into playing Joey's songs and Al's songs and Johnny's songs... nothing was a joke, nobody got short shrift. Everybody was expected to be on top of it.

Scott: That's when it's the most fun, for me, and obviously it is for Terry, too. And I've always worked that way in bands that I've been in. For me, it's always a lot more fun if everybody is really involved.

The thing is, generally, there tends to be one person that kind of ensures that that happens (laughs). And that's been Terry's job, to make sure that this comes off like a well-rounded evening. He wants everybody to be shown in their best light. And it's nice when you can do that.

Like I said, not all bands are like that. There's an awful lot of guys out there, and they have their vision and it's a pretty singular thing and the other guys are just kind of helping him get it done. There's always been a lot of confusion about that amongst the fans and whatnot, I'm sure. There's a lot of music that people naturally assume was either Joey's or Al's because they sang it, but the percentage of music that Terry is responsible for in NRBQ is very high. He's sort of like the master of ceremonies, or whatever, just kind of keeping everything going and trying to make sure that everybody is on their toes, and trying to make sure that everybody's having fun. And that's the way it still works.

You know it is interesting, from my perspective... Before I was in this band, I've always kind of been the leader. I've just sort of naturally fallen into that role. So it's been an interesting thing for me, to sort of find myself in this, figure out who I am in this band.

Because there's also all of the inevitable comparisons, which I knew were going to be there. It just so happens that Al Anderson is one of my absolute heroes. Love the way he played and I already kind of played a little bit like that when I first saw them. And so I knew that was going to be there, you know. I knew that people were going to be comparing and what not, and that's fine.

It's taken us some time, but now with the new record out and everybody contributing to this music the way that we have, I think everybody is starting to get a little more comfortable with who they are in the band.

It hasn't been an easy thing, though. You know, meeting your idols is not an easy thing to do. And not just meeting them, but you know, being friends with them. It's been a really interesting trip. And it's still evolving.

Shirley: Are you speaking about Terry in particular, or the other band members?

Scott: You know, feeling like. ... Well, let me go back. For twenty years I felt like I should be in NRBQ. And then I sort of found myself "in" NRBQ (laughs), in the Terry Adams Rock and Roll Quartet. And there's all of this expectation because I've been thinking about this for so long.

So there's a lot of self-examination going on. And obviously, I'm doing the comparisons, also. I know how good those guys are. I know how great Al is. Every one of those guys is an amazing musician. So it's difficult to not be self-conscious when your own expectations are so high, and also, the people that have paved the way for you have set the bar so very high.

It's more than just a band for me. I've learned a lot about myself and a lot about life in the three or four years that I've been doing this.

But it hasn't all been easy. Seeing Terry in the situation where he was practically starting all over. That wasn't easy for me to see. Because as far as I'm concerned, Terry is one of America's finest composers. And I feel like everyone should know about this stuff. Everyone should know about this.

The whole name change thing has been a really tough thing to go through for everybody. We knew there were going to be a lot of people that had differing opinions about it. Terry did his letter but other than that, we hadn't really had an opportunity to respond to anything that anyone said. And there's a big part of me that really wants to respond to these people. But I feel that we're not supposed to do that.

Shirley: What do you think they need to know?

Scott: We're not taking anything away from anyone. We're just adding to what's already there.

And everybody in this band loves every version of NRBQ. And all that we're doing is loving this, loving this music.

All of the albums are still there, and they're all just as great as they ever were. And they will remain there. And you'll always be able to hear every line-up of the band. Thank goodness for these great records that have been made.

And... NRBQ is EVERYTHING to Terry. It's his blood, it's his guts, it's his brain, it's his heart, it's his soul... it's his everything. The guy doesn't... you know, he doesn't have hobbies. He doesn't take vacations. He doesn't go to ball games. He doesn't go fishing. NRBQ's music is a 24-hour obsession with Terry.

Shirley: When Al left, it must have been very hard for Johnny knowing that the fans were missing him. What's that like for you?

Scott: Well, for me personally, I was welcomed into this in a pretty overwhelmingly positive way. We first started this as the Terry Adams Rock and Roll Quartet. A lot of the NRBQ die-hard fans were at all the shows and I was kind of hearing from people and also second-hand, a lot of really good things about my presence on stage.

So the only thing that's weird for me is just the fact that, you know, Conrad would kick off 'Rain at the Drive-In' and it wasn't Joey's voice that came out of my mouth. (laughter) It was mine. That was pretty intense for me for awhile. "Wow, I'm the guy now. I'm the guy that's singing 'Me and the Boys,' and 'Green Lights,' and 'Rain at the Drive-In' and 'I Want You Bad,' and all of these songs that have been so much a part of me for a long time. I still have these incredible moments playing... Sometimes Terry will call 'Little Floater' at just the right time and I'm just so moved by the fact that I'm actually up here singing this song right now, with the guy that wrote it. I don't think I'll ever really get over that. I hope not.

In some weird way I think I was sort of being groomed for this all along, not necessarily by anyone other than myself. (laughs) I was sort of grooming myself for this job for a long time.

Shirley: So Scott, you remember that when Tom was asked what he'd be doing if he wasn't a drummer, he said he'd probably be working in a convenience store. What about you Ė what would you be doing if you weren't a musician?

Scott: I don't think I'd be alive. I really don't. I don't think that I would be living. I would be dying (laughs).

I'd be dead, that's my answer. There's nothing else. It's been like that my whole life.

I started playing an instrument when I was in 3rd grade or something like that. I always say that it's really unremarkable that I ended up being a musician because everybody in my family is a musician. Everybody. My dad was a great piano player. And my mom is an amazing singer. And my sister played piano beautifully and sang beautifully and obviously you know Chris.... And I just discovered my other brother John, he never played an instrument until just recently. All of a sudden he started playing all these instruments, like autoharp and flutes...

So everybody in my family plays music and I never ever had anything but encouragement from my family in terms of what it was that I was going to do. All of the discouragement came from outside of my family. And for some reason there was plenty of it (laughs).

It was really weird. I was never allowed to play music in school. I don't know what it was, but in 5th or 6th grade I brought my guitar to school to play for my class, for my music class. And I'd taught myself how to play the guitar. I didn't play right. I only had four strings on it, but I taught myself how to play the guitar. And I don't really remember doing it, but that is an achievement of mine that I don't mind bragging about, to be totally honest (laughs). Nobody taught me how to play guitar.

I took my guitar to class and my music teacher said, "Thatís nice, Scott, but you're going to have to learn to play the proper way." And you know, that's all I ever got in school my whole life, people that didn't know how to deal with somebody that had already taught himself how to do something. It was always, "Yeah, that's nice, but you need to learn how to do it this way."

So I just thought, "Well, screw you people. I donít need you. I've already done this on my own. I'm already having fun. Iím playing music." As I said, I actually played my first bar gig, I wasn't even out of junior high.

My schooling didn't last very long. I didn't make it through high school, actually, because what's the point in being there if they won't let me do the one thing I'm interested in?

But like I said, I was really fortunate that I had this really strong family. We love each other. I'm a really lucky person because everybody in my family is just really big fans of one another. They always really believed in me. So it was really easy for me to become a musician because what else would I have done? That's what everybody else was doing. There was never any other option, especially if you're dropping out of school.

Shirley: Did you ever earn a dollar doing anything else?

Scott: I had a couple jobs when I was in high school. I worked at Steak 'n Shake in St. Louis, MO for a week, just long enough to suck all of the nitrous oxide out of the whipped cream cans (laughter). All of the Ready Whip was completely flat, and then I moved on (laughs). And I worked at Kentucky Fried Chicken for about three weeks with a friend of mine, and we got fired for smoking a joint. The only other kind of jobs I've ever had were working in record stores. That's the one thing a musician can do, if he's not playing. You can work at a record store, you can handle that (laughs). That's what Chris does.

Shirley: His own record store?

Scott: He used to run his own record store. He doesn't any longer. He works at a friend's record store now, just to get him out of the house a few days a week (laughs).

Shirley: That was very lucky for you that you didn't get squashed, that you had a great family like that...

Scott: The smartest, coolest, funniest people in the world were all in my house. What did I need those jerks for (laughter)? Most of my friends are like that, too. I'm really lucky. I have a lot of interesting, unique people in my life.

Terry Adams Interview, Part Two: Rhythm, Rockets, and the 12 Bar Blues

"Here's more of my recent conversation with Terry." -Shirley Haun

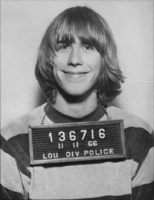

pictured: Terry in 1966

(As we resumed our conversation, Terry remembered earlier recording experiments)

Terry: Before the Webcor, I had a battery-operated small thing, 3 inch reel-to-reel. I was so into sound that the first thing I did was go out to a ditch...On our driveway there was a ditch and a pipe that went under the driveway, where the water would go. And on a dry day, I'd put the tape recorder there and go to the other side of the driveway and yell, "Man, that's some echo!" (laughs) And listen to the sound of the natural reverb, or whatever it was, the echo.

Shirley: Last time, you talked about the first three tracks of NRBQ's first album, "C'mon Everybody," "Rocket #9," and "Kentucky Slop Song," and you said, "... and that's my philosophy of rock and roll that started in my bedroom and wound up on the first album." I wonder if there's anything more that you might be able to say about your philosophy of rock and roll.

Terry: Well, "my philosophy of music as it should be played by NRBQ," is what I should have said. And it's more than rock and roll.

I don't know, sometimes I hear a song from the most unlikely source and a little light goes off in the back of my brain and it just stores it and says, "Someday that's going to be important to me. I don't know how or why." It's sort of like having a crystal ball for an arranger.

And it's happened so many times. It's not that I like the song any more than another one, but that certain songs mean something to me personally and I don't know what it is yet. It usually winds up being a part of the repertoire later on in my life. It just takes a while to figure out how it's going to fit, or when, or how it will be played, or the timing of it.

"I Got A Rocket in My Pocket," for example. I think I was 9 and we were living on a street called Ralph Avenue in Shively, Kentucky, which is a suburb, you know. Have you ever been there? It's lovely! (laughs)

By the way, that's where Girl Scout cookies were made, less than a mile from my house. You could smell the cookies being baked. You also could smell whiskey being made down there (laughs), so it was a combination. And sometimes if the wind was blowing the wrong way you could smell Dupont on the river. That wasn't a good thing. But the cookies was always a good day, smelling the cookies. So that's one of my Louisville songs, "Girl Scout Cookies," obviously.

Also, "Advice for Teenagers," you know, I lived it, there. "Rain at the Drive-in..."

Shirley: Tell me about that.

Terry: I think Louisville had more drive-ins than any other city in the US. It was just a part of everything, so it's like... $1 per carload sometimes. So there would be no sense in throwing anybody in the trunk and going in because they weren't charging you any extra anyway to get in there.

Shirley: Did it ever rain at the drive-in?

Terry: Sure it did. It was always great (laughs). But you know, I mean, it was just... that song might suggest that it was time to get naked or something but, it was just a place to... We were too young to rent motel rooms and hang out, not so much getting naked, but a place where you could park the car and talk to each other, and be with friends and not have to be worried about anything. The drive-ins were important then.

Shirley: Tell me more about "I Got A Rocket in My Pocket."

Terry: OK. I was in the backyard and my dad was washing the car in the front yard, and the sound either came over the roof of the house or around the sides (laughs), but it got to me, and I ran from the backyard up to where Dad had the car radio on, washing the car with the radio on. Back then you could have the car radio on without the ignition key. And he always listened to WTMT, which was country music and all I heard was, "I got a rocket in my pocket and the fuse is lit."

And I wanted to hear that song again but it never happened. I made the mistake of trying to find it on the rock and roll stations, because it was obviously rock and roll, but I found out later they were only playing it on the country stations because of who it was, which I'll get to later, but I spent a lot of energy and time trying to track down what that record was. And so that must have been 1958, I'm guessing.

I couldn't find it. I asked everybody I knew. "You ever heard this record? 'I got a rocket in my pocket and the fuse is lit...'" And no one knew.

I finally got up to New York City in 1967, and I started going down to Village Oldies and I asked these guys, Bleecker Bob and Broadway Al, two record experts, "Who did that record?" Neither of them knew. Nobody knew what it was and I just kept on looking for it, you know?

So I guess, I'm going to say in 1974, I decided to pick up the search again, when I was visiting Louisville, and I was in a record shop called King's Records, which was actually run by Pee Wee King's brother. Pee Wee King is a Louisville musician, on RCA Victor. I talked Tom Staley into singing one of his tunes, "Slowpoke," on one of our home tapes, as a matter of fact.

Anyway, I decided to ask Gene King because he knew a lot about music. I was spending some time there, and I just asked him. I didn't know why I had decided to ask him, [inaudible] he'd tell me. He said, "Oh, that was by a guy named Jimmy Lloyd, but his real name is Jimmy Logsdon." Well, I knew who Jimmy Logsdon was. He was a country singer, musician in Louisville, a local guy.

So now I know who did it, what label it's on... He didn't have it, by the way.

So I started searching the auction lists and finally found it in... what at the time, I don't know what that would be, back in 1974, Goldmine or something. It came up on auction, there it was. "I Got A Rocket in My Pocket" by Jimmy Lloyd.

And I kept track, in my mind, of how much I'd bid and all that, kept going up in increments, 50 cents, $1, because I couldn't miss it. And I bid $28.53 on it. It doesn't sound like a lot maybe today but in 1974 that was a lot of money to pay for a 45, to me.

I got it. I won the auction. As soon as I heard it, it was just what I thought it was. I talked Joey into singing it and we recorded it in 1975, and it eventually got released on All Hopped Up.

Now that gets to the thing about this story that I really like. I searched worldwide for something that was in Louisville in the first place, and Jimmy Logsdon lived about a mile and a half from my house the whole time. So how many times was I in town, and I didn't know it was him. (Terry begins to sing "Back In Your Own Backyard")

Shirley: This is so interesting, because as much as you had to get out of Louisville, you couldn't wait to get out, and it has maybe some negative memories for you because of how you were treated for having long hair, or playing jazz, but it really seems to have had a profound influence on your music. Do you agree with that?

Terry: I do. You know, I gotta say that you could be treated that way in Louisville at that time. You didn't have to have long hair. You just had to have an original thought (laughs) and you were punished for it. But I grew from the discouragement. I used discouragement to make it and to grow from.

But you're right. Louisville means a lot to me. I did an album with Steve Ferguson, who's from Louisville, called Louisville Sluggers. I did another record with Marshall Allen, and he's from Louisville. I could have called that record Louisville Sluggers. (laughs)

Those things come around to me. My dad had an influence on the kind of music... even though I didn't really ever associate myself with country music...but I'll never forget when he came home with the Davis Sisters' 45 of "I Forgot More Than You'll Ever Know" and "Rock-a-bye Boogie." I thought there was something kind of... almost scary about it. This was so country that it kind of triples its vibes on you.

I started to buy Davis Sisters 45s and 78s whenever I saw them, and eventually met Skeeter because Tom Ardolino, before he was in the band, we'd become friends, he called me and said that she was going to be singing at an amusement park. I drove up to Massachusetts and met her, and showed her my Davis Sisters records, and we became friends. I was originally wanting to talk to her about releasing a Davis Sisters album on Red Rooster, but then we got excited about actually recording a new album instead, and that's where that went, it became She Sings, They Play.

But anyway, back to Louisville. My dad ... Am I talking too much?

Shirley: No! Keep going.

Terry: Am I boring you?

Shirley: No, Terry, you're not boring me.

Terry: (laughs) Well, you know, I guess another one that I'm most proud of, and people don't realize it, but my dad, one of his favorite records was "I Walk the Line," by Johnny Cash. He played it everywhere we went, on jukeboxes, and my mom would get pretty aggravated with "I Walk the Line," she always made fun of it.

But the other side was called "Get Rhythm." And that's one of those, you know, the light switch goes on, you know, there's something happening in my brain. "There's something to this song." I'm not even a musician yet, but I know that's going to come into my life later as an important piece of music. And with a title like "Get Rhythm," I gotta think there's all kinds of ways to play rhythm and it doesn't have to be the Tennessee Two version. It could be something else. It became what it is and I'm still playing it to this day.

Shirley: When did you get the idea to have that different rhythm and arrangement?

Terry: I got the idea around the time we were doing Workshop, 1972, and we recorded it for Workshop, actually, and we weren't satisfied with the track. Next time we recorded it was a year or two later and it was the version of the band that had both Steve and Al on guitars. That's a great version. That's never been released but Steve does the solo and Al does the singing. I think Al was a real, obvious natural to sing and play that song and he did a hell of a job on it. But like I say, the earlier version has Steve playing the solo.

Shirley: Was "Get Rhythm" always, in your hands, the way we hear it today?

Terry: Well, yeah. That was the whole idea. "I want to play 'Get Rhythm' like this." So that's the way it was from the first time. But to get a good take of it. Sometimes the simpler things are harder to get. I don't know why.

I remember when we were doing Tiddlywinks. Every night, first thing I wanted to do was record my song "Want You To Feel Good To." It's just a blues, but it's gotta be more than the blues when you're done with it. Then we'd go on and record the other songs, but every night... just doing it again to get a good take. And maybe the fourth night, the one that's on the album, it came out.

So that's what happened with "Get Rhythm." I know we tried it for Workshop, we tried it between Workshop and All Hopped Up. We did it again for All Hopped Up. That didn't come out. It wasn't until 1977 or so that we finally got a good version on record.

Incidentally, Carl Perkins told me that after Johnny Cash heard it, he started playing it that way, too. (laughs) I don't know if that's true or not, but...

Shirley: That's a great story. What about "12 Bar Blues." Is there any connection to Louisville?

Terry: No. "12 Bar Blues" was written by a guy named Jack Butwell, who was in Florida. I was introduced to his music because Tom had a 45 called "My Port Charlotte." And I loved "My Port Charlotte." It had sort of this ridiculous cowbell part on the bridge. The drummer hits the cowbell. And I can remember torturing [Cecil Taylor's then drummer] Andrew Cyrille with it in Europe on the Carla Bley tour, like "Andrew! You gotta learn this cowbell part!" (laughs) I loved "My Port Charlotte" and that was one of Tom's records.

Donn went down to Florida with a friend for vacation and we had learned that Jack was down there on the west coast of Florida and I asked Donn, "When you get down there, could you look up Jack and tell him we're fans." Well, when he came home, he had a great surprise. He brought a 12" album called I Love Florida. He got a copy for me and one for Tom.

On that album was "12 Bar Blues." When I first heard it, it was more than the light switch going on in my head. It was instant. When I heard the original, which doesn't sound anything like my arrangement, I knew, this is going to be a big song for us, that we could really get something out of this. Instantly when I heard it, I knew how it was going to sound and...

I've talked about that a lot, I got resistance from the record label about it, you know. I don't even think Al was crazy about singing it. I had to kind of twist his arm to get him to sing it at first.

Incidentally, Jack and I had been corresponding and he had sent me some unfinished songs. I didn't tell him that we were recording "12 Bar Blues" because I wanted it to be a surprise. Sadly, he died before the release of Grooves In Orbit. He never heard it and didn't know his song was used in the NRBQ episode of The Simpsons. I think that was the episode where I did the NRBQ arrangement of "The Simpsons Theme" for the end credits, which was a challenge but wound up to be a lot of fun.

Anyway, "12 Bar Blues" is one of those things, kind of like "Get Rhythm." It starts one way and turns into something else in my head.

On our new record, I'm doing it in reverse. I've got a song by Tchaikovsky and turned it into a country tune. You'll have to hear it when it comes out (laughs).

Shirley: It's interesting to me how these, let's call them cover versions of songs that other people wrote, are as important in your repertoire as the songs that you write. For some bands, the covers are sort of things that are off-hand. How do you see performing covers of other people's songs versus your own?

Terry: I've never felt a difference because if you are really in tune with how that music can affect you personally, it's just as personal. So I don't think about that so much.

I've never minded putting other people's music on our records in place of my own if it's really affecting me personally and I feel the band can do it right.

Sometimes that not getting paid for arrangements can really sting. For example, I heard Rosemary Clooney singing "This Old House" and I got the idea to turn that into a rockabilly song. We released a sort of goofing around version, a home tape version of it, on Kick Me Hard. That arrangement got, well, basically stolen by an English artist who had a number one record for five weeks in a row in Europe and Australia with my arrangement. So I'm not getting credit and I'm not getting paid. I do resent sometimes what happens when you're arranging. You come up with an original arrangement for an older song.

I don't call them covers, by the way, because I think that has a different meaning. To play a song you didn't write doesn't mean that you're covering it.

Shirley: Do you use a different term?

Terry: Well, you're just doing the song (laughs). To me, you know, covering means, like in the 1950s, Pat Boone decided to do "Tutti Frutti" and Dot Records put it out with wider distribution than Specialty could, a week later than Little Richard's release of it, and stole the moment. Stole the radio play for "Long Tall Sally" or something, because Specialty couldn't get it on the radio. Maybe it was race stuff, or whatever. That's a cover, to me. It's a cover when the Gladiolas, Maurice Williams' song "Little Darlin'" gets picked up by the Canadian group, whatever they were called, and they are famous for it, but that's a cover.

Now if you do an original arrangement, especially years later, of somebody's song, you're actually giving that song more life, putting new life to it, for that writer, doing him a favor. You're not stealing his moment.

Shirley: So Shakin' Stevens covered "This Old House" by NRBQ?

Terry: He covered my version of us doing someone else's song (laughs). But you know, we weren't covering it.

Shirley: Understood, OK.

Terry: Am I making sense?

Shirley: Yes, you are.

Terry: So I don't make any money for Shakin' Stevens doing "This Old House." That kinda hurts, but sometimes, you know, I've run into good loyal NRBQ fans who think I'm doing some other member of the band's songs when really they're my songs, I'm just not the singer on it.

(You can see a complete list of songs that Terry's written, that have been released, by looking here.)

I've been blessed with a couple of things here. One, I had great singers around me in the band, in all the versions of the band, and those guys have been willing to sing my compositions and my ideas for me because I don't think of myself as a vocalist. I know I'm not a vocalist with a wide range. So I can have Scott or Joey or Al or Pete sing ideas, songs I didn't write that are my arrangements, or even my own songs, which I'm really grateful to them for. I've just been really blessed with that.

But the downside is people think it's their songs, so I guess I gotta get over it (laughs). I don't know if I gotta get over it or not, but you know, that's what happens.

But I like having good singers in the band, and why not have the best singers sing the right song, the best singer for the right song. I would have been singing way too much, and it would have been boring if you'd heard me singing all these ideas (laughs).

Shirley: OK. What can you tell us about another song that you guys didn't write, but that NRBQ did (laughs), "The Same Old Thing"?

Terry: Well, yeah, this is a song that I... another one of the songs where the switch goes on, for me. I'll tell you, I guess it does go back to Louisville in a sense, but... not so much Louisville, but just me as a young guy.

One of the records I got for my 10th birthday or something was called Western Movies, by a group called The Olympics. I just love that record because he mentions Maverick, and puts an "L" in it and says, "Malverick..." (laughs) "Thanks for reminding me it's time for Malverick," he says. I love that record. And somebody sings "Have Gun Will Travel." So after Western Movies, whenever I could find an Olympics record, I'd buy it.

And most times, I was disappointed, not because of the songs or their singing, but they were over-produced. I always felt that the Olympics had a problem being over-produced. By the way, they were the guys that did "Good Lovin'" that was later improved on by the Young Rascals, became a huge hit by them.

And the same goes for "The Same Old Thing," a record by them I'd bought around 1970. I thought, "This song has gotta be done somehow," I wanted to do a rawer, less produced, gospel sounding arrangement.

So when we were doing At Yankee Stadium, I didn't feel that Al had enough vocals. Al's a great singer. I thought this would be a good time to bring out "The Same Old Thing." I showed it to him, and he took to it immediately. He loved it, went with it, and he sings the crap out of it.

Shirley: Any other inspirations or arrangements you'd like to mention?

Terry: Well sure, I could. Let's see, uhh... "God Bless Us All," "Wandering Star," "You Gotta Be Loose," "Come Softly," "We Travel The Spaceways," "Daddy-O," "Honey Hush," "Be My Love," "My Hometown," "All By Myself," "It's A Sin To Tell A Lie," "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald," and a thousand more, they all have their own stories and a personal importance to me. But, well . . . there should be a book! (laughs)

So in a way it goes back to Louisville, but it's just keeping your antenna clean so that you can hear the music that may mean something to you later. I don't know where it's coming from. It could be Frank Sinatra, it could be the classics, country music, any kind of music. I never know when something can really mean something to me and how it affects the band's music.

This is what I do best, it's what I've always done, and I'm still doing it.

Shirley: The constant addition of original and outside material must help keep things fresh for the audience.

Terry: Well, I always felt that if we didn't have new songs, arrangements, a new bit, or at least a new joke, or if all else failed, a new shirt every week, we wouldn't be earning our pay.

You know, I am a notorious insomniac and now you might know why I never sleep! It's also important to keep ourselves entertained (laughs). That's why I've also always been the Activities Director.

Shirley: What's that? Tell me about it.

Terry: That's another story (laughs).

Terry Adams Interview, Part One: From the Webcor to the Stage

"I talked to Terry recently about many topics, one of which was the upcoming NRBQ Hell Night, and he was kind enough to let me tape our conversation." -Shirley Haun

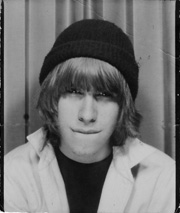

pictured: Terry at 17

Shirley: So what is NRBQ Hell Night all about?

Terry: Well, we're celebrating the origins of NRBQ, I guess. You know, 1965 was a great time for me musically. I had a jazz trio that I had been playing in, and I had always loved the blues, but that year, you couldn't deny that rock and roll and pop music were getting better and better. There was a great environment for just being excited about playing with anybody, any style of music. I got a Webcor tape recorder for Christmas in 1965 and uh . . . So I set out to fill up these tapes.

Starting in January 1966 through the end of the summer, we kept filling up these tapes with more and more stuff. Donn and I and a drummer named Charlie Craig were the core members. We, I think, were inspired by the live Cannonball Adderley recordings out on Riverside, such as The Jazz Workshop, Jazz Workshop Revisited, so we became our own audience. And Donn was the MC.

It was a lot of fun making these tapes. A guitarist named Bill Scott dropped by one day, and Rick Layman brought his C-melody saxophone and with the tape rolling, that's the day that Donn spontaneously said, "Here they are, the New Rhythm and Blues Quintet!" and we broke out in applause, and started to play. Those tapes still exist. They are part of a series of home tapes that I would like to get someone to restore, that lasted all the way until the mid-80s with the band.

And incidentally, I found the first tape where I wrote "New Rhythm and Blues Quintet" and the date on the side, and then the second one, I just put NRBQ because there wasn't enough room on the side of the tape. So anyway, that was that.

The home tapes were maybe the most enjoyable part of NRBQ, in my opinion, because . . . well, there are three ways to make music: one, for an audience, and another for professional recording, and home recording was making music for ourselves. That's why I always felt the closest to the home tapes because there we are only playing music for ourselves. Every note seems irreplaceable . . . you know, they've got a charm to them.

Shirley: Obviously the home tapes were recorded in different environments. Was the first one your bedroom, and what was the setup like, who was playing what?

Terry: I took the piano . . . I didn't want it in the living room anymore because I thought I'd be more creative by taking the piano down the hall and into my bedroom. So that's where it was. It was a Baldwin Acrosonic and it sat in my bedroom. Then I could play without interruption. We hung up a crystal microphone over the ceiling light and let it hang and brought the drums in, and . . . our horns. And that one mic picked up everything, vocals, and all the instruments.

Shirley: Did you have bass or guitar at that point?

Terry: No. Originally the core of the band was just me on piano and Charlie on drums, and Donn singing and playing trombone. I doubled on trumpet and played trumpet and piano at the same time. Both Donn and I played harmonica. So that was the original band.

During that time I substituted and was later hired as the organist in the Merseybeats USA, which was Steve Ferguson's band. The first time we played together, it was like fire. We stared at each other like the other guys didn't exist, and our playing got better and better and better. We elevated each other's playing, and outplayed each other on and on.

There were some things about being in a band that were great, but there was always management and what I call "stupid rules." (laughs) I think they tried to fine me $50 for not wearing boots. I think they had some kind of boots that was part of their...matching shirts and boots. And I refused to wear the boots and came with, you know, white sneakers or whatever.

Another time, we were recording a song Steve wrote in a studio called . . . I don't know, but the name of the studio was something like Sambo. Steve knew what he wanted. They were singing some harmony, and the producer walked out and said, "Hey! That note don't fit, don't work." And I looked up and I . . . I didn't know there was such a thing as a producer who would come in and tell a musician who'd written a song what to do. I thought that was absurd! And they were starting to bow down to this guy, and it was beautiful what they were singing. And I said, "It fits. It's a good note." And he looked at me, and he said really firmly, kind of military-like, "There are three notes to every chord, right?!" (laughs) I think he probably meant 1, 3, 5, you know. "There are three notes to every chord, right?!" And I said, "Wrong!" And I laid all ten fingers on the keys, and I said, "There's ten in that one!"

That was a showdown that I had to pay for, because I eventually got thrown out of the Merseybeats USA by their management. They were surprised when Steve went with me, because they lost their main guy. Steve went with me because we had something going together.

Anyway, while I was still in the Merseybeats, I'd said to Steve, "Why don't you come over and just play, just for the music. We've just got a thing going on in my house."

Well, you know, when Steve did play on the first home tapes, Donn and I were amazed because of what happens when you have a real guitarist who really can sing and play, and it didn't take me maybe one day or two to start to think that I could take NRBQ out professionally, take it out of the bedroom and move it out onstage.

But the idea was to keep the same philosophy: to move the bedroom to the stage. Not change the band to make it fit to the stage. We were playing for ourselves and were happy with it.

I think I made the remark, "I'm going to have a band that doesn't have fines for not wearing boots, and doesn't have to play certain songs to please audiences, and can play any song it wants, whenever it wants, regardless of what that style is." I was really passionate about that and I told Steve, and he agreed with me, that he would like to be in a band that was like that.

We played one night in Louisville, a Monday night. They had a blues night at a place called The Shack, and that was the first night I ever saw NRBQ, the name, outside a club. I don't remember exactly when that was. Probably in the summer of 1966, and it was called The Shack. The personnel that night was me, Donn, Steve, Charlie, and on bass we had Wayne King.

So by the end of the . . . We kept making great home tapes. I gotta tell you they're my favorite recordings, I think. But I guess maybe . . . I graduated from high school that June and by September, or it might have been October, Steve and I decided we were going to leave Louisville, and see what would happen out there. And we took Phil Collison with us, who naturally fell into the role of our first road manager. I had a portable organ and Steve had his guitar and we drove down to Miami.

Everything works out when you have the right positive attitude, I think. It can be magic.

So the first trip we didn't have a bass player or drummer. So we were thinking, "Well, we're in Miami now, where we want to be, but we're only half a band." And while I'm getting some gas at the gas station, on the other side of the pumps, a car pulls up with drums in it! And it's a drummer. And he knew a bass player. So we start talking and that was the first idea of what that band might be like in Miami.

We knocked around a little bit down there, didn't really play with that drummer I met whose name was Leo Vidal. And decided after some time, in November, probably, to head back to Louisville and set about to pick who the real players were going to be. Steve's idea was to choose a guy named Jimmy Orten, who had been in a band called Soul Incorporated. He was Steve's idol, vocally, and in a lot of ways. He was incredible, and I still think he's great. I had asked Charlie to come with me, but Charlie didn't want to leave town.

So we did get back down to Florida for a date that I had lined up for New Year's Eve at a place called The Happening Place, on 79th and Biscayne. And we were going to rejoin with Leo Vidal. The original bass player that Leo knew, it was just a hobby for him, we weren't really considering him. And now we had Jimmy Orten. So that was going to be the original lineup.

And unfortunately that job, that club had been closed down. They weren't allowed to open that night. The owner, Marcel Schmidt, made a phone call to a guy I can't remember the name of who had a place called The Cheetah, down in south Miami. And he said, "I've got a great band here. Unfortunately we can't open, so would you take these guys?" So yeah, they took us. We went down and set up and we played either just one weekend or two weekends . . . I think it was two weekends.

That band . . . I can't remember all the songs that we played, but we were doing songs nobody else would have done. I remember I had brought in "Hey Baby," the Don Covay song "Mercy, Mercy," a song by Richard 'Groove' Holmes, the jazz organist . . . we played a modal version of "Louie Louie," and a song by the Fugs, called "Kill for Peace." Also Steve sang "High Heeled Sneakers." Those are the songs I remember doing at The Cheetah.

The great thing about playing at The Cheetah was . . . this was finally NRBQ out there, and . . . The sad thing about it was we were too out of control to keep this band going. One thing or another happened, whether the police arrested Jimmy and Steve for vagrancy because they were sleeping in Jimmy's van outside in my driveway . . . I don't know. We had bad luck. After a couple of weekends, Steve and Jimmy decided to head back to Louisville.

I had a great lucky break at that point, because we had been on the bill with The Seven of Us, which was Joey and Frankie's band, and I had started a good friendship with their road manager, Frankie's cousin Donnie Placco. And it worked out fine, because their organist left, and there I was, subbing for another organist in another band again. But these guys were really pro, they were really great. They had a Hammond B3 with two Leslies and they had a good following.

So I joined The Seven of Us, and they were really important in my life. That's how Joey and I first met. And that got me to New York.

I stayed with them for six or seven months in 1967. I got frustrated with that band though, because as great as they were, the song selection wasn't interesting or unique. I loved their professionalism and their singing - they saved my life - but I got really frustrated artistically with the non-original approach. It was more . . . I don't know what you would call that. I talked them into getting Steve into The Seven of Us, thinking that would bring about a musical change. And it did for a short while, but it fell apart.

By the end of 1967 I was looking around to figure out what to do with myself. I took some time off to visit Donn in Philadelphia and Phil was living there also. Then Sun Ra invited me to his apartment in New York City, that story you know, and gave me "Rocket #9." That inspired me to get NRBQ going again.

So back to the home tapes, though.

Shirley: What kind of things were you doing in the bedroom?

Terry: I remember I had a special arrangement of "Desafinado" (laughs). A lot of blues, some abstract jazz . . . I'd written a song called "Hey Mr. Wise Man" . . . And just improvising. All kinds of things. We did a couple of church hymns . . . These tapes were played a lot. We listened to those tapes a lot, and so I knew, on playing it back, that we really had something. Because we were originally thinking we were just goofing off, Donn singing some blues and all that, but I knew we really had something.

That's why I felt so strongly about taking this out to the world, and what I said about not having fines for not wearing boots . . . That's just as important as the music to me. The whole narrow-minded thinking of Louisville back then, and their concept of what bands had to do and having to go through really bad experiences with producers, and . . .

The sad thing is my experience with the Merseybeats in Louisville was the beginning of me thinking that all producers were idiots. (laughs) Maybe I was partially right, but . . . It took me awhile to accept anybody's input to anything. I mean I was, like, riding shotgun all the time, like, "Nobody comes near this music. Don't even think about telling me what to do." I stood them off. That's probably how the first album happened, because we didn't have anybody trying to control us. Otherwise, we couldn't have put "C'mon Everybody," "Rocket #9" and "Kentucky Slop Song" as the first three songs on the record. "C'mon Everybody" was a really important song to me. I'd gotten it . . . I think it was another Christmas gift, in the fifth grade or something. I had heard that song only a couple of times and it wasn't Eddie Cochran's standard. I think he did a lot better with "Summertime Blues," or maybe "Sitting in the Balcony." But it meant a lot to me, and I thought it was a good song for Gadler to sing. And I brought that into the band, as well as "Rocket #9," and that's my philosophy of rock and roll that started in my bedroom and wound up on the first album.

Anyway, that's kind of what Hell Night's about. Donn and I are throwing this party, The Quartet will be there, Klem will be there, so we'll have the Whole Wheat Horns (expanded with Quentin Sharpenstein on tuba, and others). The original TKO (Tim Krekel Orchestra) will play. I want to get Charlie up there on drums and I know Steve will be there in spirit.

It's a long time ago (laughs), but it was a great time in my life.